“Not all the stories of the Troubles had been told,” Northern Irish writer Jan Carson told a crowd of about 40 people during a talk about her work in Mulhouse, France on October 21st.

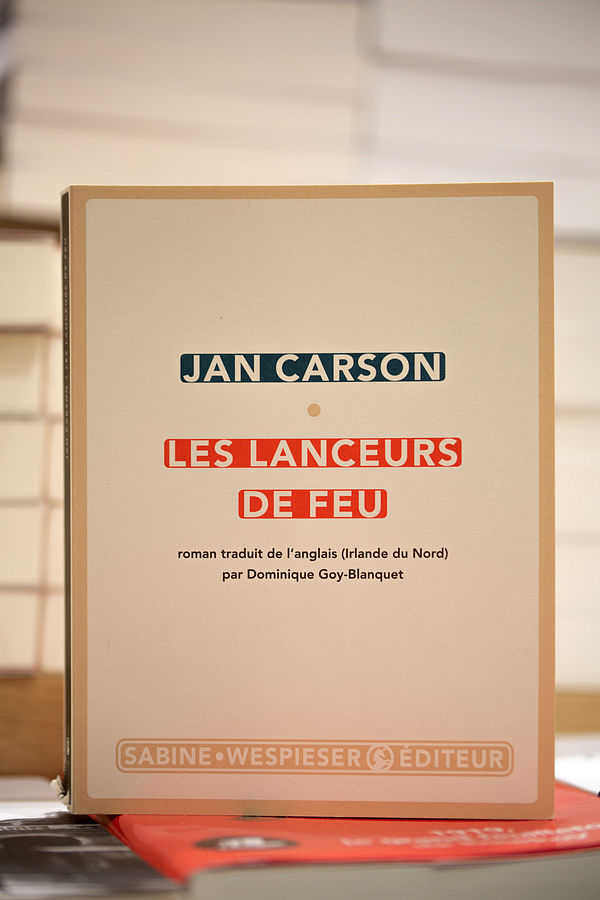

Belfast-based Carson, whose most recent novel The Fire Starters (Les Lanceurs du feu) won the European Union Prize for Literature in 2019, has been writing since 2005 and also works in the community arts. She spoke in conversation with host Antoine Jarry at the 47 Degrés Nord bookshop for about an hour and a half on the rainy Friday night.

“I brought the Irish weather with me,” she joked.

The talk was given in both French and English, interpreted by Noëlle Cuny and Victoire Noé, and was attended by a range of ages – older and younger university students, teachers and literary enthusiasts.

Isabelle, a retiree and graduate of the Université de Haute-Alsace in Mulhouse and a current Masters student at the Université de Lorraine, where Carson is several weeks into a four-month residency, praised Carson’s intelligence and charm. However, she also said that she had some trouble reconciling the “imaginary” aspects of Carson’s Fire Starters with the harsh reality of the civil war in Ireland.

Carson’s novel, which Jarry and Cuny characterized as “halfway between a fairytale and a sociological report,” is indeed different from many other stories from Northern Ireland. During the conference, thanks to questions nourished by video excerpts from famous authors such as Agatha Christie and George Saunders, Carson touched on a wide variety of topics. She spoke about her writing process (she always starts with a character), as well as the importance of telling those different stories.

A lot of Northern Irish narratives, Carson said, centered “angry, violent men,” but she wanted to provide a different perspective. By seeing their own dialect and experiences reflected in literature, the reader understands that “their story is valid.” Carson spoke about meeting lots of men like Sammy, one of two main characters in The Fire Starters, through her community work. She wanted to denounce the cultural “silence around suffering” that the brutality of the Troubles lay bare. To counter the “binary thinking” in Northern Ireland, Carson – who learned to empathize through books – aimed to write nuanced characters who weren’t “just evil.”

Finally, Carson answered some questions about upcoming screen adaptations of her works and declared that she really likes France so far – especially the “mixture of stories, identities, languages and accents” that she finds exciting. And of course, the cheese and wine.

After the talk, Carson spent time signing books and chatting with the audience, including a group of terminales, or final year students from Don Bosco High School in Landser, France. The teenagers had studied her book in their English elective class, and found Carson’s talk to be extremely “interesting” and the writer herself very “genuine.”

Kind of like Belfast, Mulhouse is also a town with many different stories and perspectives, not all of them shiny and cheerful. Carson’s emphasis on sharing the untold narratives and practicing radical empathy through literature really seemed to hit home for the Alsatian audience.

Áine Dougherty, Université de Haute Alsace